by Bill Carey

The Tennessee History Guy

President Trump wants everyone to call the large body of water south of Louisiana the Gulf of America. He says it’s a better name than the Gulf of Mexico because the body of water in question is bordered by more than just Mexico.

As a former naval flight officer and the creator of social studies booklets, I have a unique perspective on this matter. Allow me to make three points I’ve not seen made.

First of all, it’s not uncommon for countries to disagree about the name of a body of water between them. When my squadron deployed to Japan, my chart (which is what navigators call maps) had the body of water between South Korea and Japan labeled the Sea of Japan. South Koreans refer to it as the East Sea.

When we deployed to the Middle East, my chart called the body of water between Iran and Saudi Arabia the Persian Gulf. However, many residents of that part of the world refer to it as the Arabian Gulf.

What most of the world calls the Caspian Sea, the Iranians call the Mazandaran Sea.

The British refer to the strip of water between England and France as the English Channel. The French call it La Manche, which translates into “the sleeve.”

The Mediterranean Sea goes by several names. According to Wikipedia, the Turkish call it the White Sea, the Jewish call it the Great Sea, the Germans call it the Middle Sea and many inhabitants of the Middle East call it the Western Sea.

I could go on, but I think I’ve made point No 1.

The second matter I’d like to draw attention to has to do with latitude and longitude.

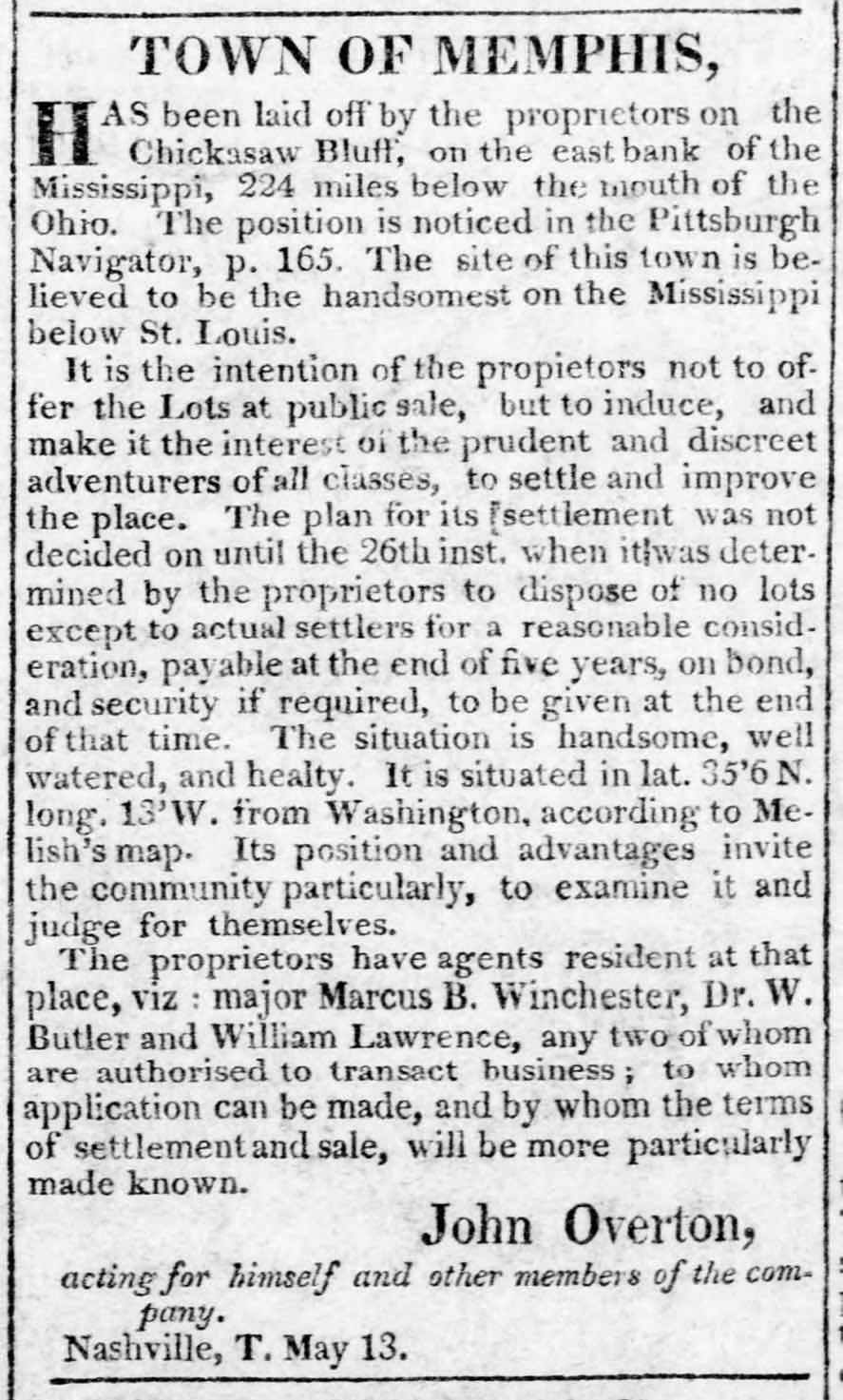

Today, longitude lines are measured west from Greenwich, England. However, longitude lines on American-made maps used to be measured from Washington, D.C. If you don’t believe me, go to the Tennessee State Library and Archives, and look at the 1796 Harris map, the 1818 Melish map, the 1832 Rhea map and the 1851 Mitchell map. All these maps have Knoxville at about 7 degrees west longitude and Nashville about 10 degrees west longitude (although some of them have degrees west from Washington labeled on the top and degrees west from Greenwich on the bottom).

But if you look at a modern map, Knoxville is about 84 degrees west and Nashville about 87 degrees west.

What accounts for this disparity?

As best I can tell, it’s because during the century after the Revolutionary War, Americans hated the British!

American maps switched to the Greenwich longitude system about when the U.S. began adopting standard time zones in the 1880s.

So it’s not just the naming of places that changes with politics and time; it’s also true of describing where things are!

The third point I’d like to make has to do with what is taught in schools. In February, a state senator proposed a resolution that “encourages Tennessee’s teachers” to call the body of water previously known as the Gulf of Mexico by the name Gulf of America. This resolution got a lot of publicity when it was proposed. But as I’m writing this column seven weeks later, its sponsor hasn’t even proposed it to committee. If it doesn’t pass committee, it won’t pass.

No reporter (unless I’ve missed something) has mentioned that Tennessee has written social studies standards that teachers and textbooks are required to adhere to. The social studies standards currently in effect were written and approved by a committee in 2017 (of which I was a member). The social studies standards that will take their place in 2026 were written and approved by a committee that met in 2023 (of which I was not a member).

If you download the current 246-page social studies standards, you will see that the words “Gulf of Mexico” appear three times: in second grade, third grade and seventh grade. Here, for instance, is social studies standard 2.13:

“Recognize that the U.S. is part of the North American continent and identify the U.S. land/water borders including Canada, Mexico, Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean and Gulf of Mexico.”

As far at the body of water south of Louisiana is concerned, the new social studies standards are similar to the current ones. The only difference is that the Gulf of Mexico appears in grades two, five and seven in the new standards (because the geography now taught in third grade is being moved to the spring of fifth grade).

Therefore, Tennessee’s social studies teachers and textbooks (in three different grades) are required to teach students that the body of water south of Louisiana is known as the Gulf of Mexico. And unless something unforeseen occurs, this situation will remain the same until the 2026 standards expire in 2034.

Many teachers will tell their students that some people, including President Trump, now call the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of America. As a member of Tennessee’s last social studies standards review committee, that’s OK with me.

Good teachers will tell their students that many bodies of water between two countries are called one thing by the inhabitants of one country and another thing by the inhabitants of the other.

Good teachers will also tell their students that early American maps used a longitude system that began in Washington, D.C. — because it took Americans a long time to forgive the British for the Revolutionary War.

If teachers tell students these things, students might learn that geographic labels are not something on which everyone agrees. Geography is not like math, where 5 + 4 = 9, and if you get something other than 9, you are simply wrong.

What people call things is decided by history and politics. Always has been, always will be.