The most overlooked factory in Tennessee history managed to survive the Great Depression and World War II, only to be annihilated by the Edsel.

Today there are three automobile assembly plants in Tennessee: Nissan in Smyrna, General Motors in Spring Hill and Volkswagen in Chattanooga.

I used to think that these three assembly plants were the only such factories in Tennessee history, other than a short-lived establishment in Nashville called Marathon Motor Works. However, a few years ago, I stumbled across an article from the 1920s about the Ford assembly plant in Memphis.

The Ford plant opened in November 1913 and within a year had 500 employees. Like all assembly plants, it didn’t make car parts, but its workers put together parts that had been made elsewhere and delivered to Memphis by rail, river and highway.

The Ford plant was one of the highest-paying manufacturers in Tennessee for decades. It was originally in a five-story building at 495 Union Ave., which later became home of the Commercial Appeal and Press-Scimitar newspapers.

Memphis Special Collections Department, University Libraries, University of Memphis

Ford left its original Union Avenue building in 1924 for a much larger plant on Riverside Drive, about 2 miles south of downtown Memphis. By 1930, the plant had nearly 2,000 employees. Some of them bought small houses in a working-class neighborhood developed near the factory known as Fordhurst.

Memphis’ 250,000-square-foot plant made more than 300 Model T’s per day in the early 1920s. It continued to make cars as the Ford company released new models such as the Model AA truck, the Model B and the Model 18.

The Great Depression caused the Memphis Ford plant to close from early 1933 until March 1935 (the closing date is hard to come by). In the late 1930s, labor strife sometimes affected the Memphis Ford plant. Sometimes the plant would shut down because of strikes at factories in the Midwest that made car parts. Sometimes, workers aligned with the United Auto Workers (UAW) would try to organize employees, and there were occasional acts of violence when they tried. That stopped in June 1941, when all Ford plants become union as a result of a management agreement with the UAW.

During World War II, new car production was halted because metal, gasoline and rubber were in short supply. Ford shifted its Memphis plant to make Pratt and Whitney aircraft engine parts and, like many Tennessee factories, hired a lot of women to work the assembly lines. After the war, the plant underwent a 75,000-square-foot expansion and was producing cars and trucks again.

Memphis Special Collections Department, University Libraries, University of Memphis

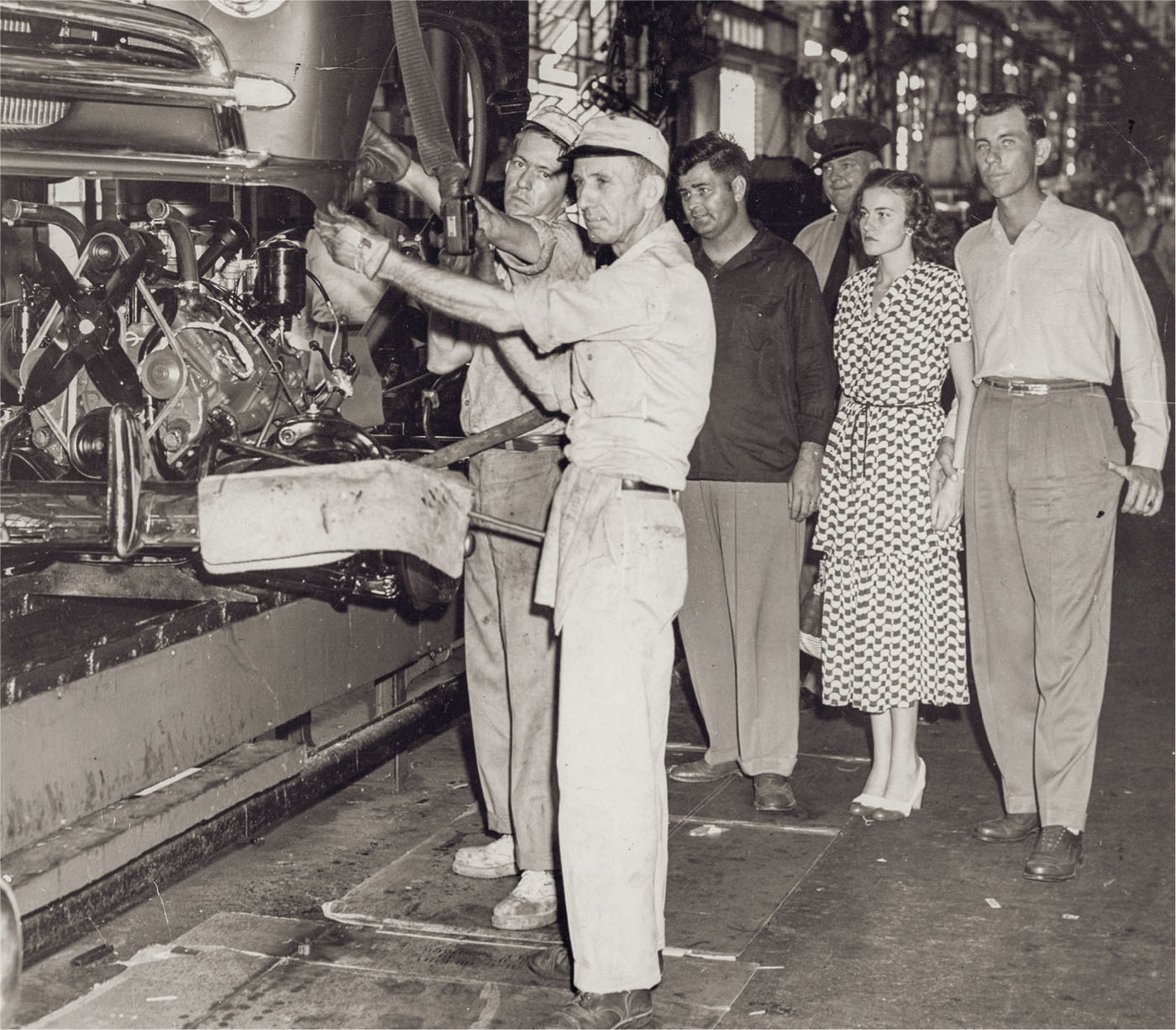

Memphis’ Ford plant continued to thrive through most of the 1950s. It was a high-profile employer whose employees gave tours to visitors and school groups and contributed to local fund drives.

Then, in 1956 and 1957, Ford invested $250 million in a sedan called the Edsel. It was named for Henry Ford’s son Edsel Ford, who was (it turns out) named for a former Vanderbilt chemistry professor. “(Edsel) was named for Dr. Edsel A. Ruddiman, a friend of the late Henry Ford, and a pharmaceutical chemist who was teaching at Vanderbilt at the time of Edsel’s birth,” the Nashville Banner explained in November 1956. (Henry Ford and Ruddiman were childhood friends. After teaching at Vanderbilt, Ruddiman worked as a chemist for Ford Motor.)

Advertisements for the Edsel car appeared in hundreds of American newspapers and magazines in August 1957, in advance of a Sept. 4 official release. The ads boasted about its powerful engine, brakes that tightened themselves, gears that shifted automatically, contour seats and even a “warning light that flashes when you exceed your pre-set speed limit.”

However, American consumers didn’t take to Edsels because of a litany of quality, design and engineering failures. “(The Edsel) was the colossal failure to which all future failures would be compared,” a New York Times op-ed piece said 50 years later.

At 4 p.m. on May 5, 1957, Ford told the 952 employees at the Memphis assembly plant that they would all be laid off a few weeks later. At the time, the company said that the factory was outdated and too small. But “the real reason for abrupt termination of the Ford assembly plant in Memphis,” wrote Press-Scimitar reporter Alfred Andersson, “was failure of the $250 million Edsel.”

On June 6, the 1,573,709th — and last — Ford ever made in Memphis rolled off the assembly line. “Everybody in the plant except the switchboard operator moved into the plant to watch the (last) car come off the line,” the Press-Scimitar reported. “Nobody said much.”

A few days later, many of the former Ford employees had a subdued picnic, paid for by union dues. A lot of the laid-off workers said they had found new jobs; some said that they had “irons in the fire”; a few talked about moving.

Today these workers and their factory are a blind spot in the world of Tennessee history. The Ford plant used to be mentioned in Memphis obituaries, but almost everyone who ever worked there died long ago. The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture has entries about Nissan, Saturn and the short-lived Marathon Car Factory but none on the Memphis Ford plant. And a few years ago, when Ford announced that it intended to build a massive electric car assembly plant in Haywood County, there was hardly any mention of the fact that the same company used to have an assembly plant nearby.