I’m aware that not everyone has connections to Vanderbilt University. But if you are interested in the Civil War, the Methodist Church or in Tennessee history, you will want to know the following:

Vanderbilt has begun to tear down McTyeire Hall, a two-story dormitory that was built in 1941. It was originally a girl’s dorm, but recent generations remember McTyeire as an international hall. I lived in McTyeire Hall when I was a junior in college, and my friends expressed sorrow on social media when Vanderbilt announced its fate.

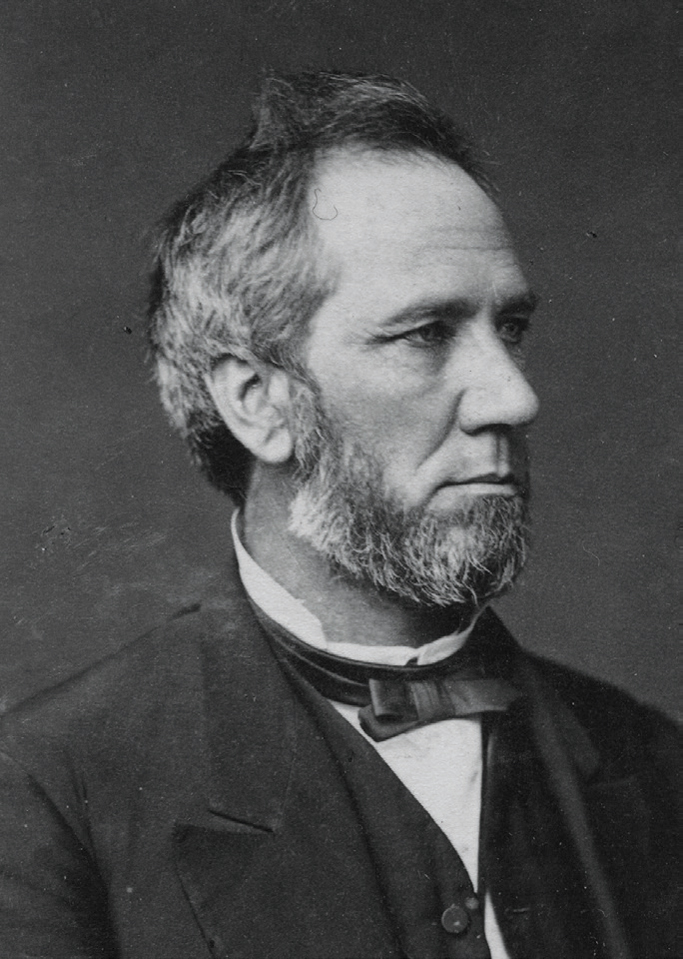

The reason I think this is of interest to people who did not go to Vanderbilt is because the school says it has no plans to name anything else after Bishop Holland McTyeire. The reason that is interesting is that I consider McTyeire to have been the founder of the university.

Vanderbilt has not said why it has no plans to name something else after McTyeire. But I suspect it’s because of his association with the Confederacy — something I wrote about extensively in my 2003 book Chancellors, Commodores and Coeds: A History of Vanderbilt University.

When the Civil War broke out, McTyeire was editor of a Southern Methodist newspaper produced in Nashville called the Christian Advocate. The Methodist Episcopal Church, South (its official name) was very pro-Confederate, as was its newspaper.

In numerous editorials and sermons, McTyeire defended slavery as an institution, using arguments that were racist (certainly by today’s standards). McTyeire also was a slaveholder himself. For many professors and students, these things alone explain why Vanderbilt should not name anything else after him.

However, when I wrote the Vanderbilt book, I was more interested in McTyeire’s war editorials because they had never been written about in a book before.

In April 1861, Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter, and President Lincoln raised a 75,000-man army to defeat the rebellious Southerners. If you think that the Methodist newspaper advised its readers to remain calm, you would be wrong. In an editorial almost certainly written by McTyeire, the paper advised its readers to prepare for a war in which God would be on the side of the South.

Here are some excerpts:

“We must meet the issue now and quit ourselves like men or be slaves hereafter. We must fight for our altars and firesides — fight, that is the word. … Witness the readiness with which Ohio and Pennsylvania and Indiana and Illinois equip regiments and put them at the service of the Black Republican party, to overrun and subjugate the South.”

“Send your gun to the blacksmith and have it fixed. Pray God there may be no occasion to use it; but there may be occasion.…He than hath no sword, let him sell his garment and buy one.”

“The North has a large population of worthless population to spare — food for powder. As a people they are by nature more cute than brave; and by profession more skilled in getting up wooden nutmegs and in handling arms. But we must not be deceived. The venom of abolitionism will make even a coward strike. …Defending our own soil and institutions, one true Southern man can chase a dozen Yankees.”

We will never know how many Southerners believed McTyeire’s editorial and enlisted in the Confederate Army, never to return home. We do know that when the U.S. Army invaded Nashville 10 months after this column was published, McTyeire fled to rural Alabama, where he remained until after the war. A year after the Civil War ended, he was ordained as a bishop in the Methodist Episcopal Church, South.

Around 1870, there was a movement in the Southern Methodist Church to start an institution of higher learning supported by the entire denomination — rather than just by the denominations in individual states. McTyeire was one of leaders in this movement, which succeeded in getting an organization chartered under the name “Central University.” For about a year, it existed in name only.

Central University would have never been built were it not for a fortuitous family connection. Bishop McTyeire’s wife, Amelia, was a cousin of the second wife of Cornelius Vanderbilt — one of the wealthiest men in America. In 1873, Holland Mc-Tyeire went to New York City to see a doctor about a health problem. While there, he stayed with his wife’s cousin and her rich husband (who was 43 years older than his second wife!).

One night, McTyeire talked Vanderbilt into giving $500,000 to the university he hoped to start. (I’m sure that Cornelius Vanderbilt — a Union man to the core — never read the editorials McTyeire wrote when the Civil War broke out.) Vanderbilt agreed, under several conditions: first, that McTyeire be named president of the school’s board of trust; second, that Vanderbilt approve the plans for campus construction; and third, that it be “in or near” Nashville.

Vanderbilt never asked that Central University be named for him. But a few weeks later, the trustees, led by McTyeire, rechristened it Vanderbilt University.

Cornelius Vanderbilt later raised his donation to $1 million. He never visited the institution named for him and died in 1877.

Holland McTyeire picked the location of the Vanderbilt campus, supervised the construction of its original buildings, picked its first chancellor and hired the school’s first professors. He also lived on the Vanderbilt campus for the rest of his life. When McTyeire died in 1889, a Chattanooga Daily Times front-page headline referred to him as the “Greatest Southern Methodist.” He was buried on campus, near the divinity school.

Times have changed. Private universities are not always as comfortable with their histories as they used to be.

When I was a student, there was a dorm on the Peabody part of the Vanderbilt campus called Confederate Hall. To summarize a long story, the school changed the dorm’s name to “Memorial Hall” in 2005 and, 11 years later, reimbursed the Daughters of the Confederacy for the donation that helped fund the dorm’s construction in the first place.

Over the years, I’ve wondered about the fate of McTyeire’s name.

Since I wrote a book about my alma mater’s history, you might ask my opinion. I think Vanderbilt should still name some building or part of its campus after its founder. But it should also put up an historic marker explaining McTyeire’s connections to the Methodist Church, slavery, the Confederacy and the university.

It bothers me that almost no Vanderbilt students know anything about why the school exists. People should also learn the difficult parts of our history. It’s only by doing so that we understand why events such as the Civil War occurred and why hundreds of thousands of Southerners went off to die convinced that God was on their side.